“The reality is that people take drugs”: What’s next for club safety?“

Following two tragic drug deaths, THE FACE talks to ravers and campaigners who want a radical change in policy across UK nightlife.

It’s midnight when I arrive at The Cause in Tottenham, North London for Wavey Garms’ 12-hour “Return” party and unsurprisingly there’s a giddy, elated, youthful crowd. They’ve been going since 6pm. Two weeks since clubs finally reopened, there’s still 16 months worth of pent-up excitement to be danced off. The smoking area is electric with high decibel conversations and dizzying levels of end-of-the-world delirium. The dance floor is heaving, but in all the best ways. I leave it, three hours later, sweaty and smiling.

On my way out, I noticed an ambulance parked outside. There was no commotion, but within a huddle of security guards, I heard someone say, “We need to call an ambulance.” This seems strange. Why would they need another one?

At 2.53am, our Uber leaves the curb on Ashley Road, N17. By 3.07am, three people are on their way to hospital.

Eight hours later, news circulated that Bill Hodgson, a 21-year-old aspiring DJ, was rushed to hospital but pronounced dead that morning.

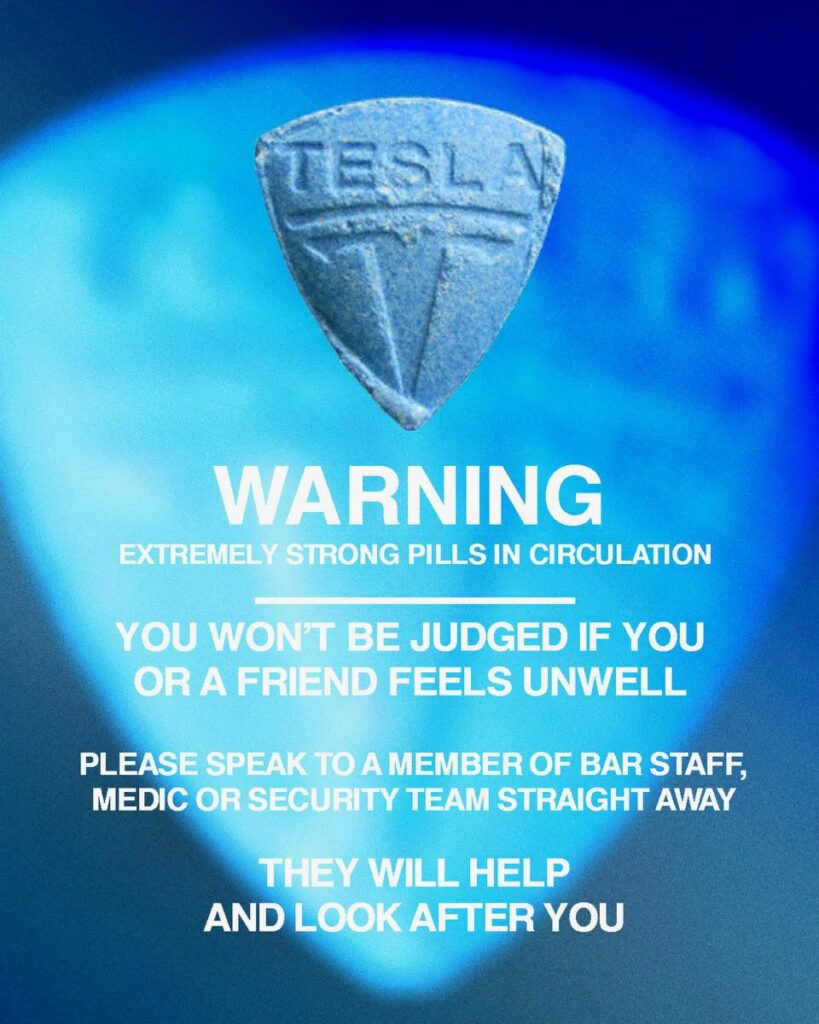

It’s been reported that Hodgson and two other partygoers — who have since recovered – had taken large blue pills emblazoned with the Tesla logo. These are presumed to contain extremely strong doses of MDMA. At the time of writing, tests to ascertain their chemical make-up are ongoing.

Since then, Bristol City Council have released their own warning about the “dangerously high-strength recreational drugs in circulation” and confirmed the death of another, as-yet unnamed, young woman in their city over the same weekend. (In Bristol, 20 others were hospitalised.)

Combined, the two deaths have reignited conversations about the future of club safety at a time when young people, so long denied a Big Night Out, might be going harder than usual.

Images of the Tesla pill have now been circulated widely across social media, along with similar warnings about a “yellow-green Spongebob pill”, also thought to be dangerously strong.

Hopefully these warnings will mean that anyone holding onto these pills will dispose of them. But the question remains: does someone always have to die before awareness is raised?

Not if people were to regularly test their drugs. Pill Report, a global database of ecstasy pills, have stated that they are currently unable to test the Blue Tesla. But it’s likely they would find upwards of 300mg of MDMA in one pill, which is considered an exceedingly high dose.

If pills were tested more regularly, and if the viral might of social media was used to spread awareness, then these kinds of warnings could be put out before they were widely bought, distributed and taken. Surely this is the way forward?

“There are people who have bought into this narrative that taking drugs is like Russian Roulette. Actually, we can take bullets out of the barrel. The risks can be greatly reduced.”

GUY JONES, SENIOR SCIENTIST AT THE LOOP

“We have to accept that people are going to take drugs on a night out,” says Ant Lehane from Volteface, an advocacy organisation working to improve the legislature surrounding harm reduction. “But people should be able to test their drugs either at home or at an event — it’s the only way we will prevent more of these kinds of deaths.”

Non-profit organisation The Loop is at the forefront of this movement. Last month they partnered with Metro newspaper for a harm reduction campaign, High Alert, which provides helpful, comprehensive and non-judgemental content on how to sesh sensibly.

The Loop have been conducting forensic testing at festivals and nightclubs for years. Back in 2016, they were behind the MAST drug checking facility — the first of its kind at a UK festival — at Secret Garden Party in Cambridge.

Rather than testing drugs that have been confiscated by police or handed in by other emergency services – those results rarely make it back to those who planned to take them – MAST (Multi Agency Safety Testing) works directly with drug takers themselves.

Guy Jones, a Senior Scientist at The Loop, stresses the importance of encouraging young people to be fussier about the drugs they ingest. “There are still so many people who have bought into this narrative that taking drugs is like Russian Roulette — you spin the barrel, you might die, you might not — but the truth is very far from that,” he says. “Actually, we can take a bunch of bullets out of the barrel. The risks can be greatly reduced.”

That’s the foundation of the Harm Reduction campaign: encouraging people to make an informed decision about what they’re putting in their bodies. It’s pragmatic, rather than preachy.

“It’s only by opening this dialogue that these kinds of services can actually make a difference,” says Lehane.

That’s why it’s so frustrating when dialogue is shut down. At time of writing, Pill Report UK’s Instagram account had been mysteriously taken down, as well as the heartfelt and emotional post made by Wavey Garms on Monday morning. “What started off as the most joyous event we’ve ever put on sadly ended in tragedy,” wrote WG founder Andres Branco in their statement.

The post went on to offer advice about safely taking drugs, which are worth repeating here: always start with a small dose, drink lots of water, and perhaps the most important thing to remember: “There will always be trained first aiders on site and you won’t get in trouble, venue staff’s first priority will always be to keep you safe.”

Only two months ago, the Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee (DCMS) of the House of Commons released a report titled “The Future of UK Music Festivals”. Based in part on an evaluation of The Loop’s drug checking services, the report specifically recognised the importance of expanding these services at festivals. It also emphasised the very pressing dangers of failing to do so this summer, post-pandemic.

“We are highly concerned that a compressed festival season, the likely circulation of high-strength, adulterated drugs and increased risk-taking after lockdown will lead to a spike in drug-related deaths at festivals this summer,” the DCMS warned. Though the focus of the report was on UK festivals, reading it back feels eerily prescient.

Jones winces as I read it back to him. Given all of these factors, is there not a grim inevitability about it? “It’s just not surprising that we would see a surge in these kinds of deaths.”

What the government report doesn’t mention is that the drugs supply chain has also been massively affected by the current political situation. “We know that the logistics networks of the world are a bit messed up at the moment,” says Jones. “And that applies to drugs as well. They’re transported through the same supply lines as legitimate goods.”

What the government report doesn’t mention is that the drugs supply chain has also been massively affected by the current political situation. “We know that the logistics networks of the world are a bit messed up at the moment,” says Jones. “And that applies to drugs as well. They’re transported through the same supply lines as legitimate goods.”

With “usual” ingredients in short supply, the likelihood of drugs being cut with dangerous chemicals is potentially higher. “All this makes a perfect storm that creates potential harm for people who have not been able to party for a year and a half.”

For Jones and everyone else I spoke to working for harm reduction, the lack of follow-up action following June’s report is deeply frustrating. “The DCMS’s specific recommendation was to make changes that would facilitate drug checking this year. And sadly, that hasn’t happened.”

It’s a common complaint. As far back as 2018, the Home Office stated that it would “not stand in the way” of drug testing services. So if these kinds of services have been sanctioned by the government, why aren’t they, well, everywhere?

“They’re not going out of their way to stand in the way, but they’re not exactly doing anything,” Jones says bitterly.

It’s this vacuum of information that has stalled progress, creating widespread confusion over the practical legality of facilitating these services. The government might say it’s okay, but not only do local councils and police forces have to agree, they also have to fund and action it themselves.

It’s like your boss saying, “I’ll leave it up to you to do the right thing,” and expecting the interns to work it out amongst themselves. The criminalised context of drugs means many people are understandably wary.

“It’s undeniable that there is a kind of symbiotic relationship between dance music and recreational drug use. And yet publicly, club owners are required to deny that.”

STEVE ROLLES, TRANSPORT DRUG POLICY FOUNDATION

Indeed, for Steve Rolles at Transform Drug Policy Foundation, it’s this legal and ethical paradox that’s the crux of the problem, particularly for those putting on parties.

“Even if club owners want to do the right thing, it’s actually really difficult to do that.”

He breaks it down: “It’s undeniable that there is a kind of symbiotic relationship between dance music and recreational drug use. This is an industry that is built on and in many ways profits on that relationship. And yet publicly, club owners are required to deny that fact [because] having a zero drug policy is often a licensing condition for an event.”

He continues: “It’s this contradiction that makes it difficult for even the most well-intentioned club owners to put in place proper harm reduction measures. Because to do so is a kind of tacit acknowledgement that drugs are being used.”

We’re still a long way off from being able to test our drugs in every nightclub, cocktail bar and pub backroom. But in the meantime, could we be checking them at home?

Jones also runs Reagent Tests UK, which sells various at-home testing kits, as does Pill Reports. RTUK’s cocaine, MDMA, and ketamine testing “multi-pack” offers 40 uses for 35 quid. That’s under a pound for every night out.

“My hope is that The Loop will put us out of business,” says Jones. “We shouldn’t have to exist, because people shouldn’t have to test their own drugs in their own homes – they should have access to better infrastructure and better expertise – but here we are.”

“If I had the chance to test my drugs before going out, I would 100 per cent do it.”

DYLAN DEHANE, BARTENDER AND RAVER

On Friday night, before we’d even had the obligatory pat-down, we were required to show a picture of a negative Covid-19 test result next to photo ID – time-stamped in the last 24 hours to be sure. If you didn’t have one, lateral flow tests were available at the door. This was the same at Fabric’s opening weekend and there’s been reports of similarly thorough procedures at major clubs up and down the country.

If Covid testing before a big night out becomes the norm, perhaps people might stop and take the time to test their drugs, too?

“I would say ‘fuck yeah!’” says 19-year-old bartender Dylan Dehane. “If I had the chance to test my drugs before going out, I would 100 per cent do it.”

“Sometimes when you’re out in a club, young people find shit on the floor, they might pick up baggies,” she admits. “It’s scary, but people just say ‘fuck it’ and do them anyway.”

Digital content creator and longtime clubber Jess Gavigan agrees that these risks are higher among inexperienced ravers. “I think when they’re younger, people are just like, ‘fuck it, let’s just get on a wave’,” the 33-year-old says. “They don’t think about what or how much they’re actually ingesting.”

Jess is an advocate for what she calls “conscious raving”. It’s about “knowing yourself, knowing your limits and not feeling the need to throw yourself into the night.”

She was at The Cause on Friday night, too. “After what’s happened, instead of replaying the narrative of ‘drugs are bad’, I think what needs to be pushed is safe raving — conscious raving.”

Before I left The Cause on Friday night, the energy was honestly electric. In the rush to return to partying after such a long hiatus, there’s a tangible sense of “Now or Never” in the air. The temptation to make each new night the biggest night ever is understandably huge. But for all of our sakes, raving safely — in every possible way — has never been more important.

So what is the future of club safety?

Rolles argues we need to think much bigger. As well as reforming licensing conditions, Transform are pushing for an end to criminalisation. Last year, they published How To Regulate Stimulants — a book that’s available for free as a PDF — and a central part of their own harm reduction approach is advocating a safe supply of legally available drugs. “Not encouraging use, but managing it.”

2021 marks 50 years since the Misuse Of Drugs Act of 1971, and Transform want it thrown out. “If we’re going to talk about drug harm reduction,” says Rolles, “we need to acknowledge the harm of prohibition and criminalisation.”

“It begins with accepting the reality that people take drugs,” Rolles insists. “That is a fact of life, and no amount of policing is ever going to stop that.”