Why Heritage Watch Brands Like Patek Phillipe and Omega Are Dusting Off Their Glamorous Backstories

Heritage has never been more important for watchmakers—even the ones that were founded less than 20 years ago.

In the world of luxury watchmaking right now, authenticity is everything. Brands pour vast resources into convincing us, the buying public, that what we’re buying into is something that will, as the adage goes, last a lifetime. More than one, in fact. What, after all, could be more authentic, more valuable, than a mechanical object containing a blend of heritage technology and cutting-edge science that comes with the promise you can pass it on to your kids? Watch companies often drive home the message—We’re the real deal! Vote for/ choose/buy us!—by repeating their backstories ad nauseam. Authenticity, to borrow a phrase, is the new oil.

In fact, plenty of luxury watch companies now employ armies of people who, like reverse prophets, mine the past to cast light on the present and then service museums that function as conduits for these stories.

Audemars Piguet’s museum in Le Brassus, Switzerland.

Iwan Baan

Take Audemars Piguet, founded in 1875. It now has a 20-person team powering its spectacular Bjarke Ingels-designed museum and heritage department. Next year will be the 50th anniversary of the brand’s totemic Royal Oak, and already the company archivists have been teasing the faithful with news that they have uncovered all manner of pertinent details on its history that slipped through the net last time they delved into the story, for its 40th.

AP is not alone. Patek Philippe, Vacheron Constantin, Omega, Jaeger-LeCoultre, IWC, Tag Heuer—the list of brands investing in museums and/or well-funded brand-heritage departments grows all the time.

Stéphane Belmont, director of brand heritage for Jaeger-LeCoultre (est. 1833), puts it like this: “[Heritage] is particularly essential in the luxury segment since history, tradition and savoir faire are key for the credibility of the brand.”

At Omega (1848), Petros Protopapas, the company’s head of brand heritage, has it this way: “It’s about conserving and preserving history to ensure that the brand, as well as fans, have the most in-depth access to the past.” Omega’s customers like stories of Speedmasters landing on the moon, Olympic records timed to the split-second and exploding James Bond watches. Protopapas gives them reason to believe.

The moon-landing exhibit at Omega’s museum in Biel, Switzerland.

JeF Briguet

Not that this is strictly a new phenomenon in watchmaking. As long ago as the 1990s, when mechanical watchmaking’s astonishing revival took hold, many realized that tapping into what they did yesterday could help shift what they were selling today. Tag Heuer had previously mothballed its Monaco and Carrera models, but on re-releasing them in the late 1990s it was at pains to remind us of its ties to Steve McQueen and the golden age of motorsport. It worked, didn’t it?

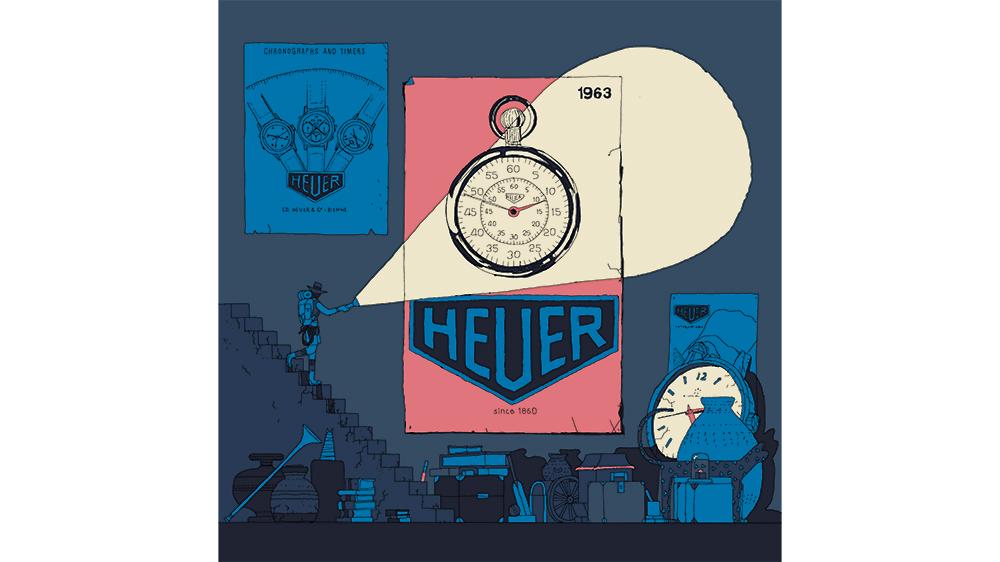

But, as if to prove the theory of its value today, the past hasn’t always been treated this way. Catherine Eberlé-Devaux, now at Bulgari but formerly Tag Heuer’s heritage director, once told me that during the 1980s and 1990s when Tag Heuer was twice bought and sold, new generations of execs felt archives, stashed in weighty box files rather than the cloud, were unnecessary baggage. So they threw them away. Her job, she said, was to rebuild them, which meant scouring the earth for copies of old manuals, print ads and books.

Because of the perceived value of heritage in the world of watches, the status of the brand-heritage director is increasing exponentially. Their work sells watches. And not just for the brands they represent. Auction houses and pre-owned sellers are benefitting from it, too. Just look at how secondary-market prices of Royal Oaks and Nautiluses have spiked in recent years. And of course, this being a circular economy, the brands get plenty of splashback, too.

Catherine Eberlé-Devaux, Tag heuer’s brand heritage director, scoured the earth for discarded ads, manuals and more.

Illustration by Celyn

Sébastian Vivas, Audemars Piguet’s entertainingly bookish heritage-and-museum director, understands the sexiness of his work, describing it as “a constant adventure” and “like a perpetual treasure hunt.” Next year, when we hear the story of how Gérald Genta created the Royal Oak in a way we’ve never heard it before, we will no doubt see a commensurate bump in sales.

Omega’s Protopapas says, “A genuine story gives people confidence in your brand. It matters because it serves as a living proof of a brand’s authenticity. With so many commercial choices available, it’s the real story, the true history, that makes the difference.”

Such is the value of a good heritage story that even new-generation brands find themselves obliged to buy back into a past they have nothing to do with. British watch company Bremont is a master of this, couching its story through timepieces inspired by the Wright Flyer, HMS Victory and the Enigma machine—cultural markers that in some cases predate the brand’s first watch of 2007 by hundreds of years. The company’s subsequent success gives wind to the idea that if you haven’t got heritage of your own, you’d be smart to borrow someone else’s.

But let’s face it: Talk of authenticity and heritage is a veneer in itself, hiding the reality that what we’re really on about here is nostalgia, which has a new currency when the world is going to hell in a handcart. Earlier this year, Cartier introduced a new version of the Tank Cintrée, a faithful reboot of a piece that debuted a century ago—when, as won’t have escaped anyone’s attention, the world was heading into the Roaring Twenties.

There’s no reason why such a design should herald another period of prosperity, but then that’s not the point. The appeal is in the suggestion that it could. Authenticity, stripped bare, is fodder for our misty-eyed appetite for optimism, and for hope. Cynical marketing approach or not, most of us will welcome a little hope.

Robin Swithinbank is a frequent contributor to The New York Times, the Financial Times and GQ. He writes from the UK