Jack O’Connell strips it all back

Jack be nimble, Jack be quick, Jack get your kit off! The Derby Lad plays a stellar polar explorer in intense BBC Arctic thriller The North Water.

Eight years ago, not long after he turned 23, Jack O’Connell was on the other side of the world, filming the role of a lifetime under the direction of Angelina Jolie. To say it almost killed him would be an exaggeration. But the actor did go as far as he possibly could to portray a man who ended up resembling the walking dead.

In Unbroken, based on the best-selling biography of the same name, the kid from Derby was playing Louis Zamperini, a real-life American World War Two hero. After being shot down over the Pacific, the former Olympic runner survived 47 days on a life-raft, then two-and-a-half years in unfathomably cruel Japanese prisoner-of-war slave camps.

O’Connell was fit – as a handy schoolboy footballer, he’d had trials at Derby County until knee injuries kiboshed that dream when he was 16 (he remains a “fanatic” about the club, and still watches “every kick”, despite the Rams’ currently parlous fortunes under manager Wayne Rooney).

But he had to use that fitness to become unfit. He went on a starvation diet for three months, limiting his daily intake to 800 calories (the average bloke needs 2500 a day), his weight dropping from 11 stone to eight-and-a-half. He even risked looking like a dodgy goth by dying his hair black.

“There were times on that raft when I just didn’t have the energy,” he told me at the time. “So I was sneaking the odd biscuit. I just thought: ‘I need something…’ I kind of blacked out once or twice. I am a production liability,” he acknowledged with a thin smile.

His sacrifice was worth it. Unbroken, released in late 2014, was brilliant, a fitting tribute to the incredible Zamperini (who died, aged 97, shortly before the film’s release). For his performance, O’Connell – a working class kid who was acting on telly in The Bill aged 15 and left school after his GCSEs – won the BAFTA Rising Star Award.

Only four years earlier, he’d been working in Bristol, nearly losing consciousness for altogether different reasons. He was hard-partying Jack the Lad James Cook in the third and fourth seasons of Channel 4’s teen drama Skins, following fellow future leading men Daniel Kaluuya, Dev Patel and Nicholas Hoult.

So it had already been some journey when O’Connell and I met in East London in early 2014, not long after he’d finished the four-month Australian shoot for Unbroken. We were mainly discussing David Mackenzie’s prison drama Starred Up. After his turn as a psychopathic gang leader in indie horror Eden Lake (2008), and the urban vigilante viciousness of Harry Brown (2009), it was another slice of hardcore uproar for the fast-up-and-coming actor.

To play ultra-violent young offender Eric, O’Connell became wirily muscled, and went deep into character. He spent time with an ex-convict who “was actually dubbed Wandsworth’s Most Violent Inmate 2005”, with the immersion process further aided by filming – and having in-cell sleepovers – in Belfast’s decommissioned Crumlin Road Gaol, an institution he called a “museum” of the Troubles.

“You’d go into the cells and see the political messages,” he said. “And sometimes not political. I walked into a padded cell, and someone had written in pencil: ‘Kill me.’”

But as he explains now, all that rigour is a no-brainer.

“In order to properly inhabit someone, it has to be all-encompassing,” O’Connell states with customary conviction. “Using [physicality] as part of your tool-set is vital, because it’s me job to convince people en masse, hopefully, that I am this fella in this story.

“And to be honest, it’s quite an enjoyable part of the job, being able to bring all that to a role. If you’ve got to get fit, or lose weight, or learn to ride a horse, that’s my department. Personally, I feel [doing] anything less than that is a shortcoming.”

When Jack O’Connell goes there for a role, then, he really goes there. So it is in his newest drama, The North Water – literally this time, too.

The BBC five-part thriller is set in 1859, aboard a whaler plying the freezing northern waters of the title. O’Connell and heavyweight cast-mates Stephen Graham (his old pal from Shane Meadows’ 2006 film This Is England) and Colin Farrell filmed for six weeks aboard a replica ship in the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard in the Arctic Ocean. Less green screen, more blue skin.

“Just one less thing to pretend, isn’t it?” shrugs O’Connell of a production that foregrounded onscreen authenticity over onset comfort. “Instead of having to remind yourself that you’re cold if you’re on a sound-stage in a studio, layered up, under lights and you’re probably hot – and just having that to play off as a constant was so rewarding.

“It was such a luxury to be free of having to [pretend to] play the elements, because they’re already there. So your reaction’s only gonna be an organic one,” adds the man who acts as the viewers’ conscience – an ex-army surgeon with a dubious military record in Raj-era India – in a series that almost capsizes under the weight of grim, beardy, seafaring gnarliness.

“There was this level of having each other’s backs – in the extremity of the environment it was important to keep an eye on each other. You had polar bears and fucking walruses looming around. So with that added threat, it ramped up the intensity.”

It was tough, but it had to be, with a tight shooting schedule only adding to the pressures on the cast and crew. “But credit to the people involved because we got it – and we got it good.”

Episode one ends, shortly after a mass, hand-to-hand cull of seals – Farrell is grimly compelling as the hulking, hirsute harpoonist with a murderous relish for killing mammals large and small – with a cliff-hanger. Or, even, an ice-hanger: O’Connell plunging into the Arctic waters, hanging on for dear life. How was it filming that, er, lateral floe test?

“Ah, I’ve got to be honest, that was a water tank in Budapest!” he admits with a grin. “But! In exchange for that truth, I’ll tell you that we did have the opportunity to do a bit of a polar plunge. When the ship wasn’t sailing about, it was moored, and we jumped in. You wore that like a badge, actually.

“I did it more than once,” he adds, “and it was phenomenal! Your body’s reaction to that sudden dip in temperature! You just go into this auto-charge type feeling. And you come out and you’re warm! You’re stood on the ice, out the water, bollock‑o, but warm!”

Woah, rewind. O’Connell went in bollock-naked?

“Weeeell, I had me boxers on.”

I think in the Arctic that still counts as naked.

“Yeah, yeah!” he agrees with a laugh. “Just for a dip! In and out, to feel the benefits. It’s supposed to be good for you.”

O’Connell – Derbyshire accent still front-and-centre, amiable but focused, cheerfully hailing me with an “alright, bud?” – is zooming in from his newly purchased home in Islington, North London. He turned 31 the previous weekend. How did he celebrate?

“I was over in the West Country seeing friends and family. It was wholesome – start early and finish early!”

He’s more keen, it seems, to be at home. It’s taken him three years to buy his first place of his own (although in his twenties, he and his mum did go halves on a place in Derby), a process prolonged by him constantly being away filming, the cluster-fuck that was 2020 (“all me prospective work disappeared”) and, well, estate agents.

Now, though, “I’m loving it, man. I’m dead happy with the area. People are dead chatty round here. And there’s no need to leave!” he says brightly. Overtly, this resolutely down-to-earth leading man is pointing out the proper neighbourhood vibes of the area around Angel tube station. Covertly, he’s making a nod to the fact that when he’s here, it’s not for long, so when he is, he doesn’t want to go anywhere.

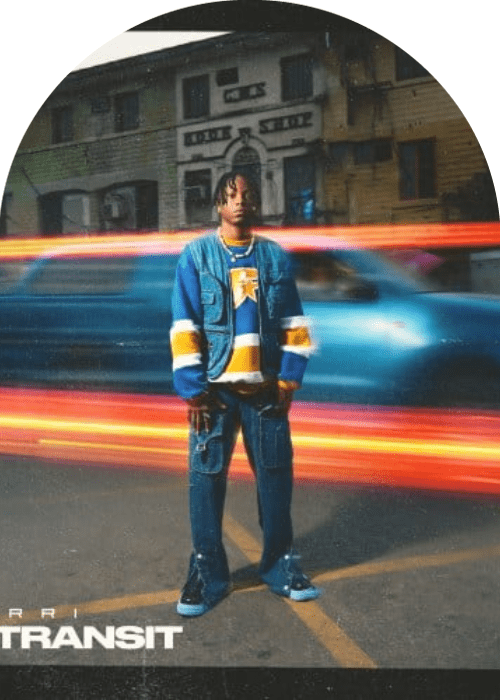

JACK O’CONNELL

Does it feel like a proper grown-up moment, finally being a property owner?

“Ha ha, yeah, deffo! Mind you, me mum’s got a key so she’s in and out of here more than I am.”

Don’t tell us she’s doing your cleaning, Jack, ’cause that’s not cool.

“She puts it on herself to do it,” he insists, squirming slightly. “I don’t ask her to! But she’s a clean-freak, me mum, so that has its advantages.”

O’Connell (who has a younger sister) and his mum are very close, undoubtedly more so since his dad – who worked 24 years in the railway industry that was a key employer in Derbyshire – died of pancreatic cancer when O’Connell was 18. Close enough, in fact, that she’s actually his manager.

“It’s not like one of these ‘mumagers,’” he clarifies, the very Hollywood word clearly awkward in his mouth. “She’s not, like, telling me what jobs to pick, nothing creative. She just goes in between the different representatives and what have you. She used to work in the refunds department of an airline, British Midland, so in terms of the office stuff and going over books and accounts, she brought that to the table.

“And you know what, it’s great – and it’s great to be able to do that because she hasn’t got to go out working, and she can just work from home. It works.”

His mum was his wingwoman when we met seven years ago, too. I tell him that it’s reassuring that he’s stuck with her – and not “gone LA” – as his career has sky-rocketed. After Starred Up came great gigs like nail-biting Troubles-set British indie ’71 (2014); 2017 western Godless, the previous prestige Netflix series from The Queen’s Gambit creator Scott Frank; and Hollywood films including 2016 crime thriller Money Monster with Julia Roberts and George Clooney, and 2019 political thriller Seberg with Kristen Stewart.

“Yeah, I mean, listen, she just makes it easier. She’s dead-on. I think she wants to have that influence. And she wouldn’t be letting anyone rip me off. They wouldn’t be getting away with it. She still has that mentality of where we grew up in Derby – keep the purse strings tight, and everything else. It’s good to have that. Our roots are still very much embedded in where we’re from.”

Still, where he comes from, kids like him – working class, from the “regions”, no contacts “in the industry” – aren’t meant to do jobs like this. Compounding that, O’Connell was a bit of a jack-the-lad in his teenage years, falling into booze-related aggro that, he once told me, meant “I haven’t done time, but only by the skin of me teeth”.

JACK O’CONNELL

Salvation in part came via the Television Workshop in Nottingham, a community non-profit where he acted – for free – twice weekly from the age of 13. There he looked up to the kids a couple of years ahead of him, future stars like Line of Duty’s Vicky McClure, Game of Thrones’ Joe Dempsie and This Is England’s Michael Socha.

“There was this attitude at the Workshop that ran right through all of the more senior members there,” he remembers. “And it was this approach to your work that you wanted to have – a fearlessness, the ability to just throw yourself into anything and give it your all, without restriction.

“That’ll never leave me. I wouldn’t be the actor I am today without having had those training years. And I think you can recognise a Workshop actor because there is that common streak of that attitude that you bring to your work. I’m eternally proud to hail from there.”

That background also informs his fierce work ethic.

“Typically our class of people are not offered these types of careers. So that means a huge deal to me, that I can turn up, represent and ask the question: why are the arts so exclusive? It shouldn’t be an expensive vocation to be educated on. But for some reason it is. So that gives me a real sense of personal purpose.”

Still, he knows the opportunities he had are even harder to come by in post- (yeah, right) austerity Britain. These days O’Connell wouldn’t know what advice to give a young lad like him “who wants to get into this line of work. And that frustrates me.”

That drive and focus – and sense of success hard-won – are there in all his work. It’s another reason why Jack O’Connell goes there: he’ll never take anything, any job, for granted.

When we meet, he can’t talk about his next gig, but it’s announced a week later. O’Connell is about to begin shooting a new, “female-focused” Netflix film adaptation of D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Emma Corrin – revelational as Princess Diana in The Crown – is Lady Chatterley.

And though his role hasn’t been confirmed, it seems certain that O’Connell will be the bit-of-rough gamekeeper with whom she embarks on a “torrid affair”. With a cast like that, expect next-level intensity from this fresh take on an English literature classic.

JACK O’CONNELL

He can, though, talk about the job he just finished shooting in Morocco 10 days prior to our interview. Broadcasting early next year, SAS Rogue Heroes is another BBC series, in which O’Connell plays another real-life World War Two legend. This time he’s Paddy Mayne, a founder member of the Special Air Service, while Conor Swindells (Sex Education) is David Stirling, the elite regiment’s creator, and Alfie Allen (Game of Thrones) is Jock Lewes, their first training officer.

“It was a fascinating one, I enjoyed every minute. But it was the toughest one yet, and I don’t say that lightly.”

Really? Even after the starvation, and the jail-time, and the bollock‑o Arctic dips?

“Oh yeah,” he replies, nodding soberly. “We were filming in very extreme conditions, extreme heat, we weren’t able to eat well, people were going down – and we had a lot to do. It was an achievement for everyone. But the First AD [Assistant Director], for him to get to the end and still be on his two feet – that’s up there with one of the most monumental efforts I’ve seen from anyone while I’ve been doing this malarkey.”

Jack O’Connell has now been doing this malarkey for over half his life, and there’s no sign of it slowing up. Like he said, lads like him aren’t meant to have careers like this, successful or otherwise. But now he’s into his thirties, does he think he had to sacrifice his personal life for work?

“I tell you, me twenties were bonkers,” he says with a shake of his head, as if casting his mind back to experiences ranging from those rager student parties in Bristol and the measly biscuits on a raft in the Pacific.

“I got to fulfil all the things I wanted to do with work, but that did come with sacrifices – you don’t go to Ibiza with your mates for a 21st. Typically in this job, the summer is especially busy, so you miss out on a lot of summer arrangements.”

But that, he acknowledges, is part of the gig, particularly when you’re as all-in as he is. Still, now he’s a bit older, he doesn’t hanker after the partying so much.

“I’m not a twentysomething anymore, so what’s left is a reinforced feeling of devotion. ’Cause I take so much from doing a job, and trying to do it well. It’s become a real passion and something that rewards me. So the sacrifices were worth it.”

The North Water is on BBC2 and iPlayer from 9th September