BALLS: when art and footie collide

Today, OOF magazine has opened its first permanent gallery space next to the Tottenham Hotspur Stadium, featuring work by artists Jazz Grant, Sarah Lucas and JJ Guest. Its purpose? To question our relationship with the beautiful game, one art piece at a time.

It’s been three short years since art and football magazine OOF was founded by good mates Eddy Frankel, Time Out’s chief art critic, and veteran London curators Justin and Jennie Hammond. In that time, the trio have brought their vision of the beautiful game as a microcosm of society to the world via the medium they know and love most: art.

With three exhibitions across London and contributions from the likes of Juergen Teller, Juno Calypso and Turner Prize winner Chris Ofili under their belt so far, the logical next step for Frankel and the Hammonds was to find a more permanent, tangible space through which to preserve and celebrate the community spirit that helps bring OOF to life.

Enter OOF Gallery. After 12 months of hard graft, it has fittingly found a home in Warmington House, a Georgian-style townhouse owned by Spurs right next door to the stadium in Tottenham. As a Grade II-listed building, it couldn’t be demolished when construction for the stadium began in 2015, so a decision was made to simply build around it.

Art and football might not sound like the most natural pairing, but debunking this preconception is what OOF is all about, with community driving its founders forward, head first.

“We like the idea of art people coming to Tottenham,” Frankel, a lifelong Spurs fan, says, “but more appealing than that is everyday football fans being able to have an art experience, and for the local community to have a high quality art gallery in their area. We’re also trying to get that community engaged. There are four schools around the stadium. How often do they get taken to the Tate or the National Gallery? Probably not that often.”

Marcus Harvey, Victoria, 2008

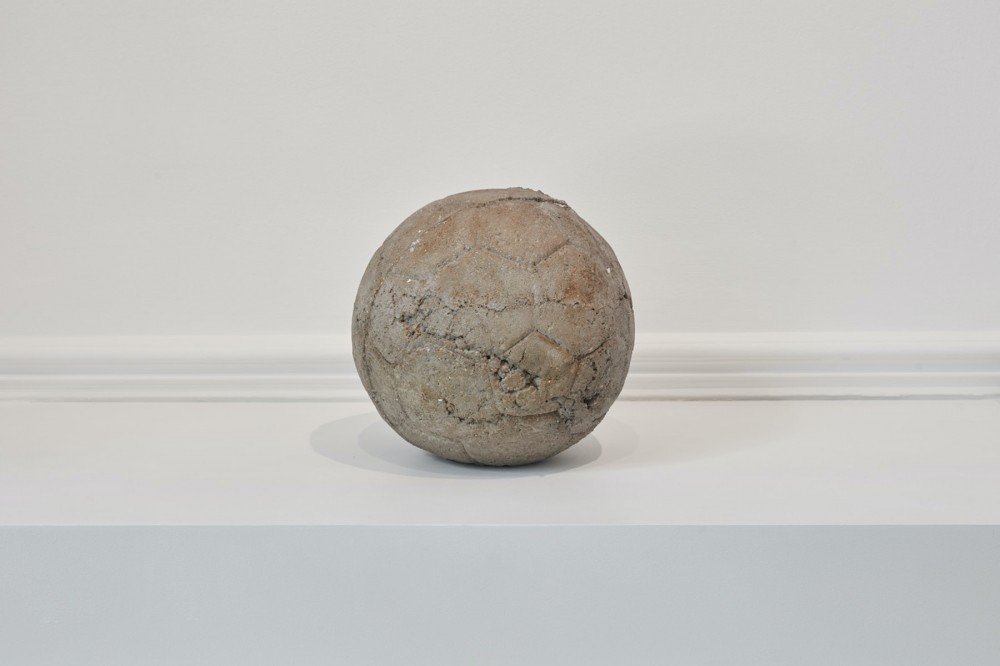

Kieran Leach, The First Ball, 2020

Nicola Costantino, Male Nipples Soccer Ball, Chocolate and Peach, 2000

Dominic Watson, Kipple #2: Mitre Delta, Nike Cortez, 2021

Jazz Grant, Canary in a Coal Mine, 2021

Hank Willis Thomas, Endless Column III, 2017

Sarah Lucas, World Cup Again, 2002

Lana Locke, Celery FC, 2012

JJ Guest, Balls, 2021

As we are yet to recover from Euros fever (or is it heartache?), OOF Gallery’s inaugural exhibition, aptly titled BALLS, offers a bit of respite beyond football-themed art, like paintings of your favourite footballer or “a diagram of the perfect goal”, as Frankel puts it.

Instead, it seeks to bring footie art to Tottenham in an intelligible, wholly accessible way. “Then if you chose to, you can dig deeper,” he continues. “We’ve also hired three young people through the government’s Kickstarter scheme; their job is to help [visitors] navigate the art and figure it all out.”

While BALLS features big art names like Sarah Lucas, Marcus Harvey and Abigail Lane, who were all part of the late-’80s-to-mid-’90s Young British Artist (YBA) movement, OOF has also commissioned emerging artists to put their own spin on the exhibition’s overarching concept: to create useless footballs, ones you can’t kick because they’re, well, works of art.

Some sculptures on display are nostalgic, looking at youth and memory through a rose-tinted lens. London-born artist Lana Locke buried a bronze stick of celery into a football, in reference to a famous – and very rude – Chelsea chant. It was her way of expressing a longing for “the heady atmosphere of going to a match, but also the weird sexism and intensely male aspects of it,” Frankel explains.

Then you’ve got pieces more akin to “surreal punchlines”, which shine in their sharp humour and simplicity: a football with nipples on each of the pentagon panels by Argentinian artist Nicola Costantino is boldly on display, as is the world’s longest football, courtesy of Frenchman Laurent Perbos. Collage-master Jazz Grant’s contribution involves an old ’70s football torn apart and rearranged in the shape of DNA strands, covered with images of hooliganism from the era.

“As a young Black artist, it’s her way of looking at how intimidating and scary football can be, especially in the wake of things like the racist reaction to footballers after the Euros,” Frankel says. Football might be in England’s genetic makeup, but so is racism. The sooner the UK reckons with that, the better.

“Throughout the whole show, every single football tells a different story,” he continues. Case in point with JJ Guest, a young gay artist who crafted “a beautiful pair of ceramic bollocks in a net” from fine bone porcelain: “He’s a young man who felt like there wasn’t a place for his sexuality in football, and probably in wider society as well.”

In other corners of the space, sculptor Lindsey Mendick explores new glazing techniques, while Sarah Lucas pays homage to Arsenal player Charlie George, who grew up on the same estate as the artist in Holloway, North London. Meanwhile, Marcus Harvey’s giant centrepiece, Victoria, depicts a deflated football in what Frankel describes as “a searing critique of English identity”.

OOF Gallery has big plans for community outreach and workshops with kids in the area, namely by spearheading an artist residency at Warmington House. “We don’t want to just be plonking a bunch of fancy art in the middle of Tottenham,” Frankel says. “I live here, I care about the area, I don’t want to gentrify it. Fairly soon, we’ll be inviting artists for three-month stints to come and work here.”

“It’s really fun to be able to put works out that are critical and engaged in things, in a football stadium – that and the community are integral to what we’re doing.”