Tremaine Emory’s new collection: “I want it to bring pride to the African diaspora in London”“

Denim Tears are not enough: with his new collection for London Fashion Week, Tremaine Emory shines a light on colonialism, colours and uncomfortable British history.

“Doubling back to the UK…the originators of colonialism this September…”

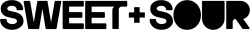

So ran the caption on a 24th August Instagram post by Denim Tears. The image was of a cream sweater featuring the Union Jack, but rendered in the red, green, gold and black of the Pan-African flag.

On 3rd September, a new post featured a pair of white jeans emblazoned with another re-coloured take on Britain’s national flag, this one in black, green and brown. The caption: “Windrush ting in london in a few weeks…’stay tuned’ 1 9 4 8 – pants Union Jack”.

These were the first visual drops of Tremaine Emory’s latest Denim Tears project. Clearly there’s a story to unpack here. 1948, for example, is the year passenger liner Empire Windrush docked in London with the first immigrants from Jamaica, then a British colony, who had been persuaded to come to the UK to fill a postwar labour shortage.

Hence the name of the collection the designer is unveiling at London Fashion Week: Empire Windrush Nineteen Forty Eight. A title freighted with meaning, for garments lifted by history.

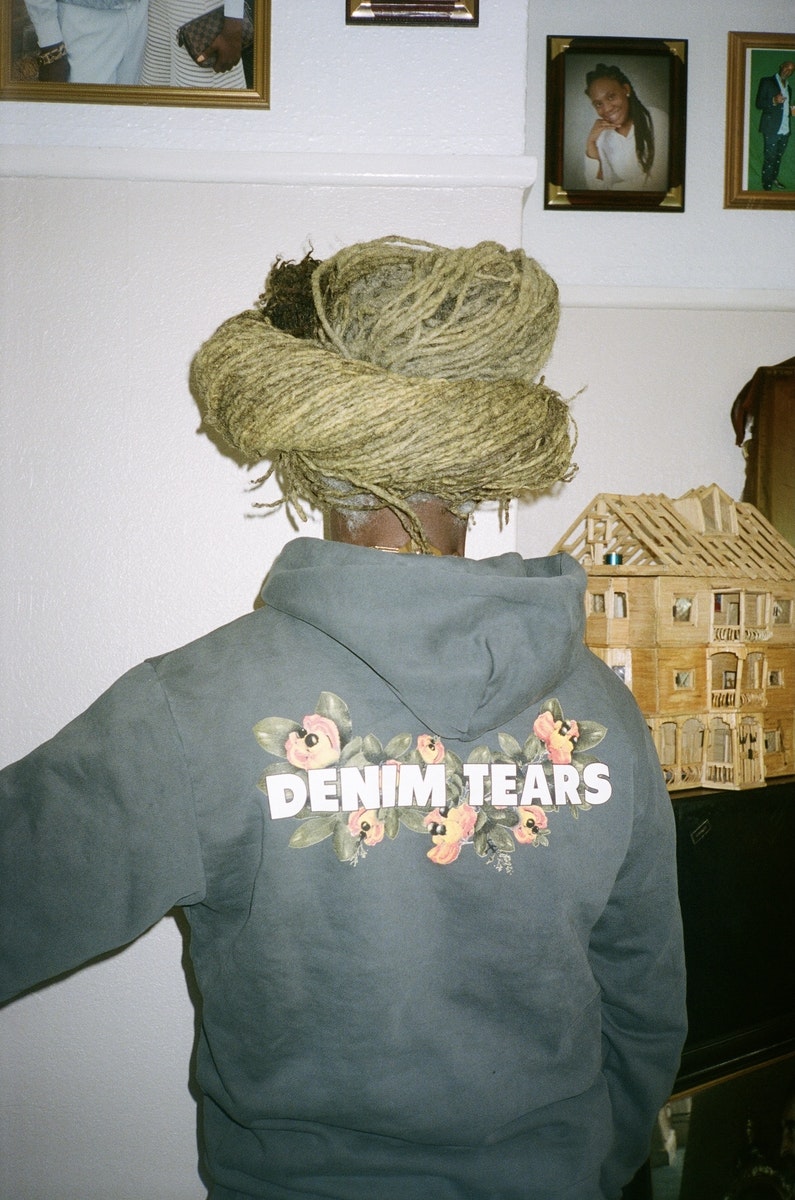

This 20-piece collaboration is the work of Los Angeles-based Emory, London artist/curator Khalid Wildman and Stavros Karelis, owner of Machine‑A, the London store where the collection launches exclusively tomorrow (17th September) on the first day of LFW.

All three have known each other, they echo over a four-way Zoom conversation, for “many years”.

“Tremaine always follows his vision – he’s a multi-disciplinary artist as far as I see him,” says Karelis. “I find his vision very inspirational and honest.”

Talking of Wildman, Emory pays it forward. “The first thing that grabbed me about Khalid is the way he pontificates about things, whether it be on his Twitter or in a conversation. His intellect and his humour piqued my interest. And the longer I know him, the more depth I find and the more I learn.”

Returning the compliment, Wildman praises Denim Tears as “a storytelling platform” with an “ability to tell particular stories through garments or art”.

But for all that mutual respect, this story looms bigger and runs deeper.

Those two items of clothing and two brief captions spoke volumes: about British colonialism, the legacy of empire, the long shadow – stain – of slavery on the UK. “Great Britain” may not have been the actual originators of colonialism. But it did have the largest empire in history, encompassing at its early 20th century peak a quarter of the world’s population and a quarter of the land area. And its roots are dark.

Visit Washington’s National Museum of African American History and Culture and, in the basement exhibition, the facts are stark. During the 300-plus years of the transatlantic slave trade, from the 16th century to the 19th, Britain shipped 3.1 million Africans to the New World colonies. Only Portugal trafficked more human beings – 3.9 million.

Meanwhile, last year, as statues were rocked or toppled around the country, the National Trust found that a third of its 93 stately homes had links to Britain’s colonial and slave-owning past. As explored in a brilliant recent New Yorker article, Britain’s Idyllic Country Houses Reveal a Darker History, these palaces of white prosperity and gentility were built on the shackled backs of Black Africans.

Into this hugely long overdue reckoning and debate about British imperial history comes Empire Windrush Nineteen Forty Eight.

For Emory, the seeds of the concept were planted when he read an article about Wildman’s new concept space and gallery, January Tamarind. As Wildman described it in an interview earlier this year, “my intention was to have a space where there’s focus on works from the African diaspora, Black artists and creatives. But that conversation for me is interconnected to an overarching concept about beautiful things from humans from wherever.”

As Emory sees it, January Tamarind “was a good part of Khalid synthesised into a space with art and furniture of the African diaspora. I was blown away and I just knew I had to do something with him.”

The pair’s first project was Denim Tears’ spring 2021 collaboration with Scandinavian brand Our Legacy. Wildman styled and photographed the capsule collection, casting Brixton artist and cultural flag-bearer Dennis Wilson as a model.

Having been asked by Karelis – a champion of fashion with a story to tell – to create something new and special, now, Emory and Wildman have already completed their next move: a focused range of clothing foregrounding race and politics, and asking difficult questions on beautiful pieces.

Tremaine, this new collection began, as Khalid put it in one of his collection notes, “with a conversation about Windrush and evolved into an abstract approach to familiarity with Jamaica as the focus”. Can you unpack that for us please?

Emory: That was the jump off. A big part of this collection for me is inspired by Steve McQueen’s Small Axe series. [Then also by] just my experiences living in London for almost eight years and hearing the stories of my friends of first generation Jamaican descent, Nigerian descent, Ghanaian descent – all the diasporas, coming to London, how they’ve been treated back home, how they feel, the effects of colonialism back home, the effects of colonialism in the UK. How do they feel as far as race, class, politics are concerned? [What is] the pain and the beauty [in those]? Because it’s not all bad and it’s not all good.

It’s also an extension of what I’ve done interpreting Marcus Garvey’s flag [as seen on Denim Tears’ 2020 Converse collaboration], putting it on garments and telling the stories of 1619 in America [the date the first enslaved Africans arrived in Virginia] and, now, of 1948 in the UK. The flag was also inspired by Chris Ofili’s [Union Black] flag and David Hammons’ [African-American] flag.

So that’s the brief I gave Khalid. And he and we took it somewhere else.

Khalid, what was your thinking in terms of creating this new take on the Union Jack?

Wildman: I was inspired by generations of my family. I grew up Jamaican in Brixton – my family came over during the Windrush period. As Tremaine and I were going back and forth, it was almost like reliving the stories of my family I was told growing up, their personal experiences. So my focus was an injection of a Jamaican spirit that I feel lives through the UK.

A lot of my previous projects [focus on] the spaces in between and the untold stories. That’s [there] even in the context of my own ideas of identity, growing up in Brixton, not necessarily feeling very British at all, and then slowly adopting the idea that so many generations of my family had been here and built what is known as Britain. Acknowledging that in flag form seemed like a commemoration.

Stavros, why does telling stories – and this story in particular – through clothes matter to you?

Karelis: What Tremaine and Khalid have to say is really important. But when it comes to clothes, this is how a lot of people connect and are informed. It starts a dialogue about these important matters around us that we should learn about. And with Machine‑A, we are involved with lots of young people and super-young consumers – they come in and experience our clothes in different ways. It’s very important for them to connect with, ask questions, be informed and have a conversation around those subjects.

How important is it, Tremaine, that fashion unpacks and questions history like this?

Emory: It’s important to me that I do it. Denim Tears is a storytelling art project. Currently it uses clothing to be a bridge to tell these stories. I don’t know what it holds in the future.

But I don’t find fashion important at all. I find personal style important in culture and community. Fashion, ready-to-wear, couture and sportswear are advents of late capitalism, so I don’t have much to do with it. I have a lot to do with style, storytelling and community.

That’s part of the reason I was down to do stuff with Stavros. Brands ask me to do stuff every week, but he’s just a real dude.

Khalid, one of your references is stylist and artist Dennis Wilson, who models both the Our Legacy collection and this new one. What’s his resonance for you?

Wildman: Anyone who’s grown up in the Jamaican community in South London will know Dennis, probably more for his style. It’s another story “in between” – these connecting individuals, like Tremaine and Stavros, have a particular energy and spirit that exists before it reaches a wider audience. To me, Dennis Wilson is that exact same kind of character. He embodied for me what an artist was, even if no one else outside of Brixton knew him.

Tremaine, could you break down for us the design of the sweater?

Emory: I was like, “Khalid, I want to do pants with the Union Jack on them, but with the Black gaze on it.” That was my brief. I was trying to imagine someone of Jamaican descent, or anyone of African descent, in Brixton in the ’90s wearing Moschino Union Jack pants. So I wanted to match those things together.

Each pair of the pants are hand-painted in Los Angeles. It’s my denim that I’ve cut, 1954 cut white Levi’s, plain janes [jeans]. Khalid and I designed them together.

And the sweater?

Emory: It’s a play on my Tyson Beckford sweater, which features the Pan-African flag and is a play on the Polo Ralph Lauren sweater. Again, it’s putting a patina of the Black gaze over the white gaze. Because you can’t erase the white gaze. These two things have to live together. Like the colonialists and the colonised, white and Black people, we can’t erase each other. They’re inside us, we’re inside them. And we have to learn how to live together for this world to progress.

So playing with those colours in the Union Jack in that sweater, that’s what that is.

TREMAINE EMORY

Stavros, what do you want this collection and your shop’s presentation of it to bring to London Fashion Week?

Karelis: It’s the right moment to think and discuss and have this physical interaction with the collection in the space of Machine‑A. We want people to see Khalid’s artwork and Tremaine’s vision. That physical element is really important.

During London Fashion Week, I always try to do something unique and create an environment that’s different, where people can experience something they don’t expect. It’s extremely rare to find collections, designers or individuals who have something important to say. Tremaine and Khalid do, so I hope people experience that.

Tremaine, the same question: what do you want Empire Windrush Nineteen Forty Eight to bring to LFW?

Emory: I want it to bring pride to the African diaspora in London. You guys run this shit. This country is nothing without you. Don’t ever think for a second they did you a favour in any kind of way.

And I really want to get people talking more about the hypocrisies of Britain’s colonial past, it’s connections to American slavery, and the hypocrisy of it now, from Brexit to repatriating people of [Afro-Caribbean] descent. I want to start these conversations. I want to make people feel uncomfortable.

And what about anyone lucky enough to snag one of these limited-edition items?

Emory: I want a young, whatever-coloured kid to walk into some posh establishment, or down a street in Mayfair, with that sweater on, and for someone to ask them a question because they feel uncomfortable: ‘Why are you wearing that?’ Then a conversation starts.

Denim Tears’ Empire Windrush Nineteen Forty Eight is available exclusively from Machine‑A, 13 Brewer Street, London W1F ORH, as part of a bespoke installation created by Khalid Wildman, from 17th September