Junglist: the heady tale of a music genre’s mid-’90s explosion

Penned by photographer Eddie Otchere and writer Andrew Green in 1995, the cult classic novel told the story of how Jungle shaped the Black British music scene. Now, it’s being republished.

It’s 1994 in Peckham, London. You’re in the club, ’ed’s spinning, drink’s been spilt, a fight’s just broken out – and the weekend’s barely begun.

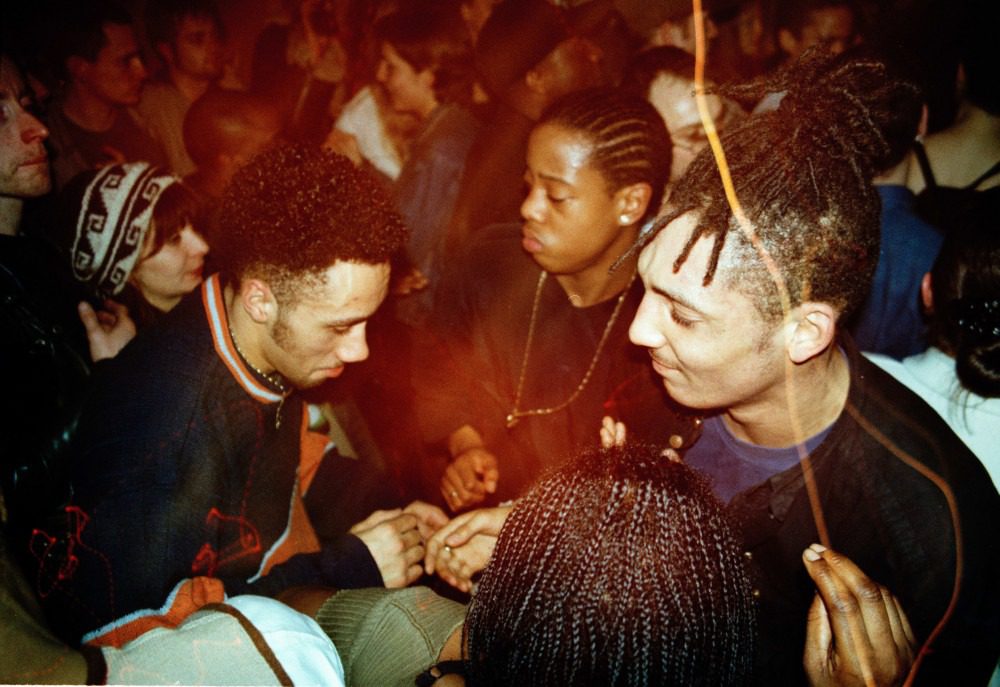

Twenty-six years ago, photographer Eddie Otchere and writer Andrew Green released their seminal novel, Junglist – under pen names James T. Kirk and Two Fingas – a quick-talking, coming-of-age cocktail tracing the highs and lows of four young Black men in mid-90s London.

Set during the Jungle music explosion in the summer of ’94, the stream-of-consciousness prose is darkly funny, poetic and pulsating, laced with Jamaican patois, shattering basslines and an authentic telling of inner-city life. Now, it’s being republished for the first time.

“I think the real motivation behind it was the fact that, on Amazon, the price of the book went up to like £247,” Otchere says over Zoom, before cutting out.

“Last time I looked on Amazon, there was a copy of the original, the first printing of it, selling for £2.5k or something,” Green adds.

“Once you’re in that universe, you’re in the realm of a cult classic – obviously they kind of wanted to cash in on it,” Otchere says after his connection fixes up.

Kemistry & Storm

At the time of its original release, London was a divided city. White ravers were sweating in the city’s surrounding fields during the acid house reign of the late ’80s and early ’90s, while the city’s Black youth were partying to breakbeat and hip-hop in underground clubs in Hackney, Peckham and Brixton. Racism was rife, with the police force targeting young Black people, and the country was a mess politically, following Thatcher’s long, long reign. There was mass unemployment, a housing crisis and a dark recession.

But like great music movements in previous decades, a cultural shift was bubbling from the strife. Developing out of the rave and sound system culture of the ’90s, Jungle was born, characterised by heady breakbeats, synth effects, soulful melodies and deep basslines.

Originally confined to pirate radio stations, Jungle’s trajectory to becoming a defining British music scene began underground, birthed by Black twenty-somethings. It quickly found its way into the mainstream, with artists like M‑Beat, DJ Rap, Mickey Finn and Jumpin Jack Frost regularly featuring on London’s Kiss 100, the first legal radio station dedicated to music of Black origin. But by 1995, even BBC Radio 1 had its own weekly Jungle show, One in the Jungle.

“The whole point about Jungle was that it was never going to be in a club that was in central London – it was always in Hackney or Peckham,” Otchere says of the genre’s early beginnings. “It felt like we’d got somewhere when we started to have Jungle nights in central London.”

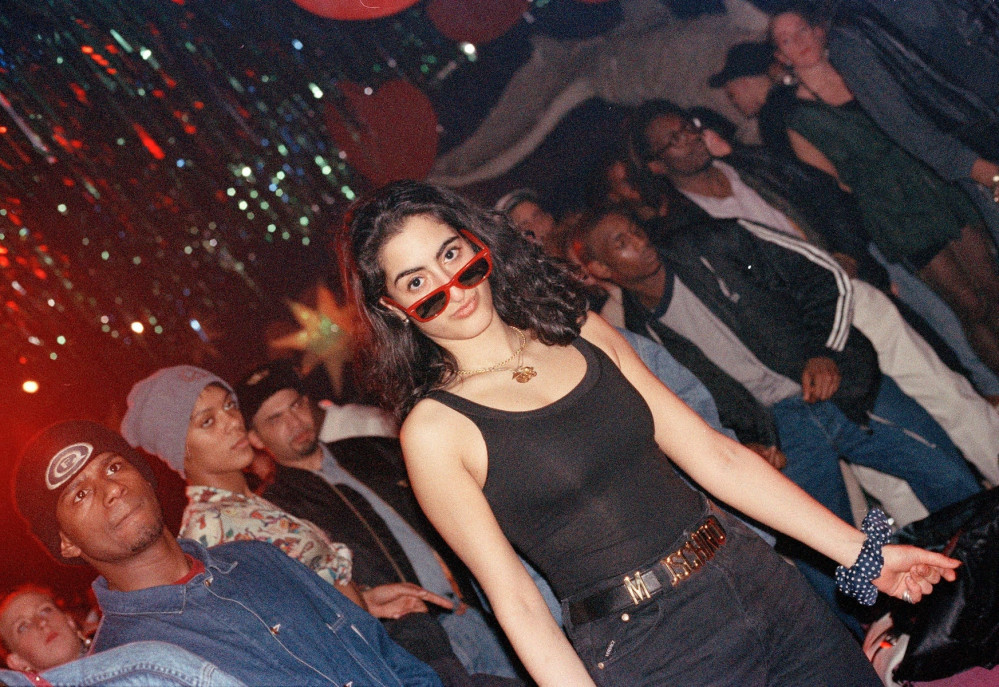

At this point, Green reflects on how the genre became “acceptable and respectable” enough for these nights to happen in the first place. But it still needed to be exciting and enticing to get people through the doors. Jungleheads would turn up in slickly dressed groups, queue around the corners of Soho’s streets and await a sweat-soaked night raving to 180bpm – or thereabouts.

“Suddenly, [Jungle was big enough] for club owners to say, actually, you know what, we’re going to have this night on in the centre of town.”

For Otchere, it was The End – the nightclub, that is – that put Jungle and its brother, drum and bass, on the map. “Friday nights at The End set it out to be a global phenomenon,” he says. “Only in London could you get that sound.” And more recently, pre-Covid, Otchere caught the feelings all over again when he went to see Andy C play at East London’s XOYO during his residency. “He brought that back. I’m grateful we’ve still got heads that can bring that spirit back, because once it became central London – once we arrived – it became a global thing. It’s like we set the tempo.”

And of course, it was about unity – groups of young men and women dancing in sweet harmony under one roof. At its core, isn’t that what Jungle is all about? Not everyone thought so – namely, the conservatives. “They know what it does. If you put a group of humans in a room that don’t know each other and might normally be slightly antagonistic towards each other, and have them dancing for an hour, psychologically, they get reprogrammed and they get on,” Otchere says with pure passion.

He remembers a turning point in the summer of ’88. “We broke up for school and all the fucking racist white kids went about their business. We got into fights and all the rest of it,” he says. “By the time they came back in September, they were completely different human beings. They’ve been out raving, they’d taken pills.” Suddenly, they were no longer tethered to fighting in football clubs.

“They had long hair and they wanted to talk about music. That’s what happens when you take ignorant fuckers and get them dancing. They actually start to think again.”

Otchere, who’d snap partiers in the mid-’90s scene, knows this all too well. His extensive archive is as much a time capsule as it is an illustration of the power of a youth movement that went from the deep underground to a stratospheric unifier. People of all backgrounds, ages, races and religions coming together, dressed up, smiling and having a good time.

As well, Andrew Green sees the book as an opportunity to celebrate Black stories. “I’d like Junglist to be remembered as a piece that encourages and enables others to write about their own experience,” he says. “Not for it to be depressing or gang-related, where it has to be about punishment and Black pain. There is something joyous about telling a story about the teenage experience, which to a certain extent is universal.”

“I want everyone to remember the value of friends,” Eddie Otchere adds.

With its republishing, Junglist becomes more universal still. There’s no need to fork out £247 for a copy – Eddie and Andrew have got you.

Junglist is available to buy now for £10.99 at repeaterbooks.com