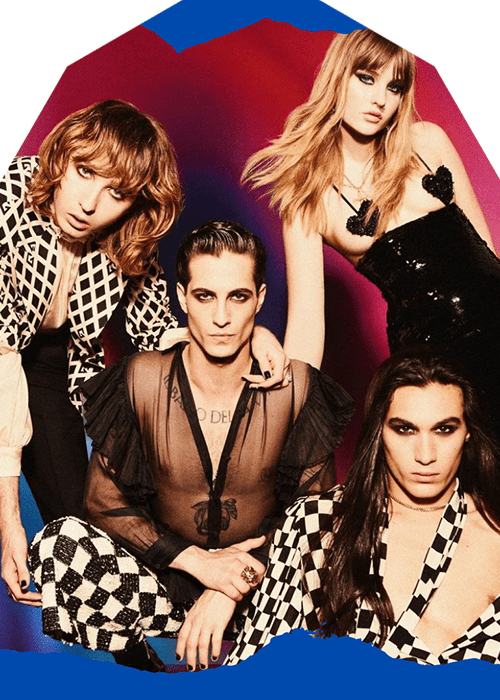

Simeon Barclay on exclusion, Black mythology and Britain’s past

The artist opened his latest exhibition, England’s Lost Camelot, last weekend. After labouring on the artworks through both lockdown and nerves, he’s ready to show the world how he’s rewritten (sorry, repainted) the country’s history.

Simeon Barclay might have already taken over the Tate Britain with his monumental, multimedia show The Hero Wears Clay Shoes in 2017, but he still gets all jittery making new work.

Especially this time around, as he prepared his latest exhibition, England’s Lost Camelot, over the long course of lockdown. He likens the process to memories of being young, getting an A4 sheet of paper and controlling and dominating the sheets with whatever it was he wanted to appear on it. Putting pen to paper, if you will.

“I look at it in the same way as when I get the opportunity to show in a gallery,” the Leeds-born artist, 46, says. “This is the first time in two years that I have been given the opportunity to approach a blank canvas and articulate stuff that I’ve been thinking about. Not just in preparation for it, but physically in the space.”

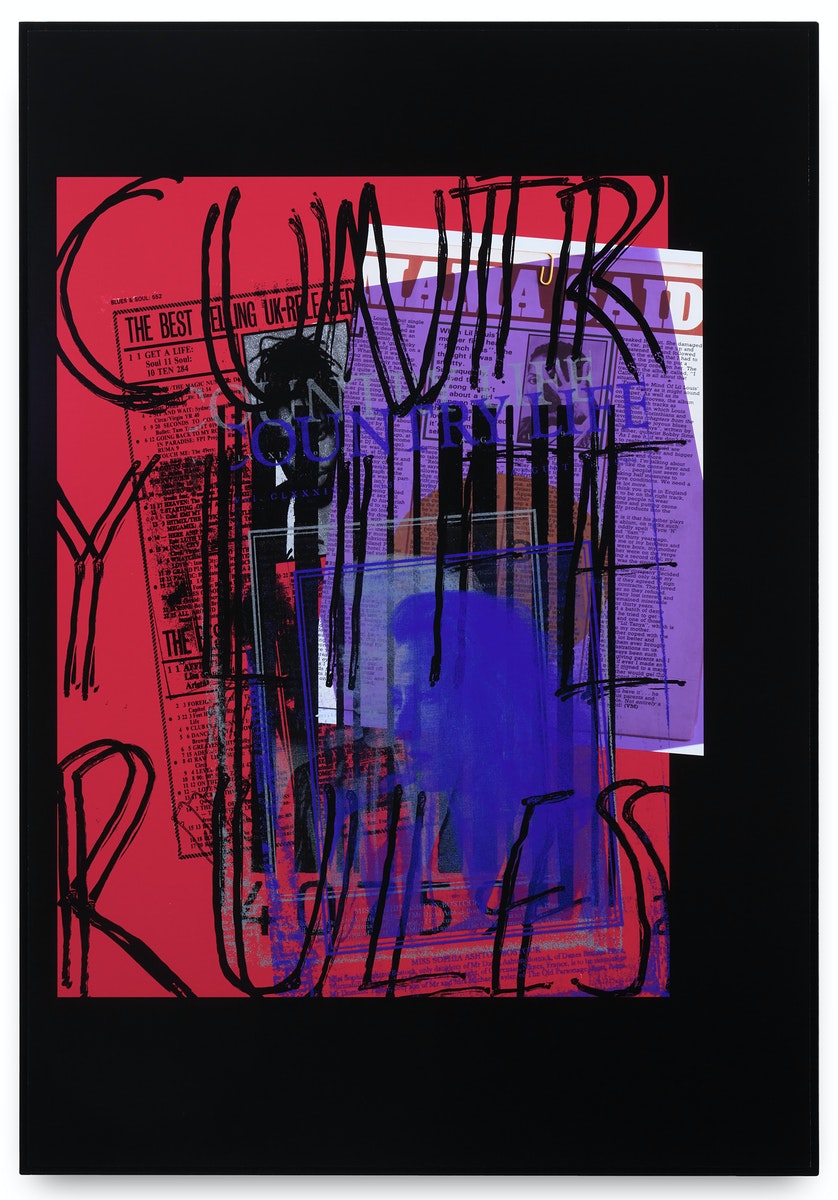

Barclay’s past work references many of the same themes: masculinity, growing up as a young Black man in the North of England, unemployment, gender expectations, memories and nostalgia. And often told through appropriated images of footballers, muscle cars, comic strips and newspaper cut-outs, his latest work doesn’t stray too far. This time, however, he hones in on Black folklore and Black political resistance, primarily as a method to understand the nature of belonging in the world around him.

“I was really interested in folkloric traditions,” he says, before referencing mythological Warhammer characters, Knights of the Realms – nobles who have proven their skill and valour in combat in the fantasy game. “Growing up, maybe I thought there was a reality that was embedded in England’s history. As time has gone on, I feel that this was concocted out of a certain myth.”

In England’s Lost Camelot he explores the country’s cultural legacy, “uniting all these Anglo-Saxon histories, Celtic history and various other histories, and creating a sort of mythology”. In a sense, for him, it felt like a branding exercise, a way for him to “give a face” to what he wanted Britain’s history to look like, what it could be and how it could be seen.

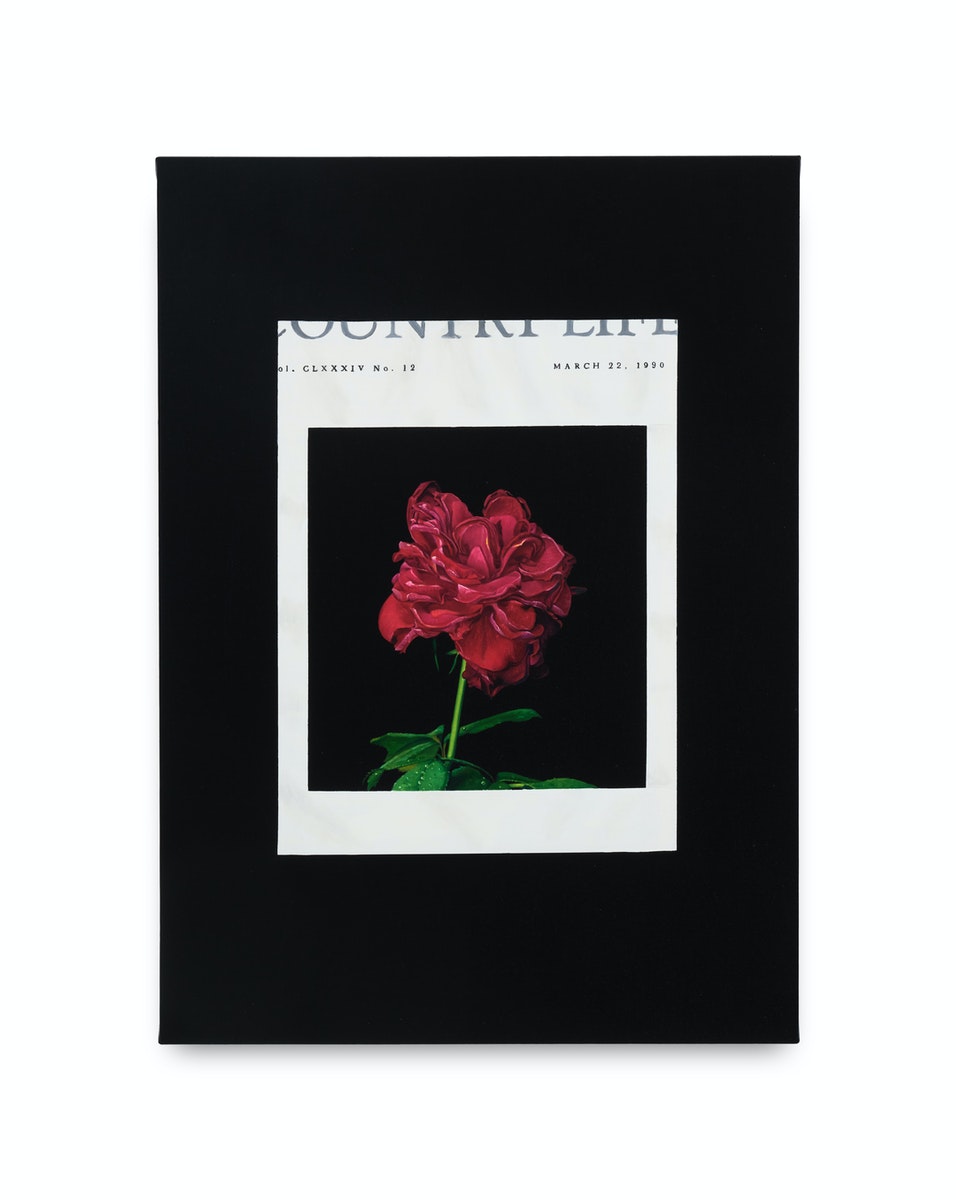

With that in mind, the new work features artefacts and imagery borrowed from British folklore, interspersed with collages constructed from the artist’s own collection of contemporary ephemera, such as a screen-printed image of a couple snogging with “It’s a black thing” written boldly underneath and various roses scattered throughout the pieces. Barclay also looked to clippings of 19th-century pamphlet The Boy’s Own Paper and its cultural relevance to Britain’s public schools.

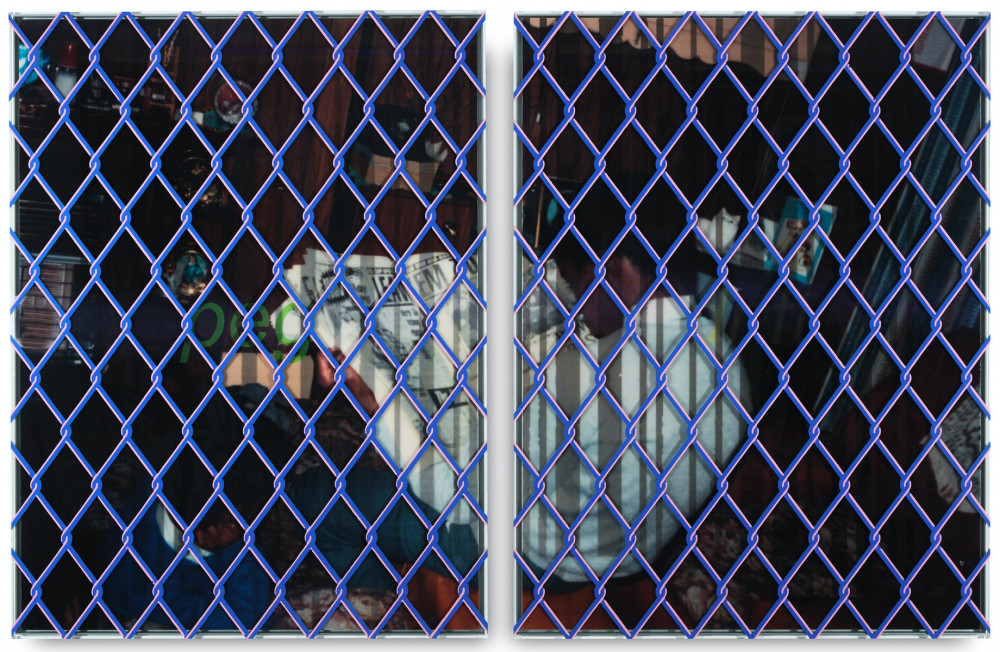

It formed themes of exclusion throughout the work, with Barclay using barcodes and fences to obstruct the viewer’s sight. “I started thinking about public schools and the types of gentlemen that came through those schools,” he says. “It created a hierarchy of individuals that was exclusionary.”

After getting through the creative process, Barclay’s jitters are all but a thing of the past. He’s feeling confident, looking forward to his next show, bound to be a hit. “After spending so long on this exhibition, my head’s kind of taken over,” he says. “Now, the flower’s are starting to die and we’re waving goodbye to summer!”

At least we’ve got some stellar art to tide us over.